Scientific name: Pinus ponderosa Douglas ex C.Lawson

Large center cone is from Pinus sabiniana. The two bottom are from ponderosas, the left one is fresh off the tree, just fell as the author was hiking by this fall, and the right one was an older one found on the ground.

Common name: ponderosa pine

Family: Pinaceae (Pine)

Article by Peggy Rudberg

One of our favorite decorative materials for the approaching holiday season is pine cones. While pine cones may seem common, they are much more remarkable than they appear. But more on that later.

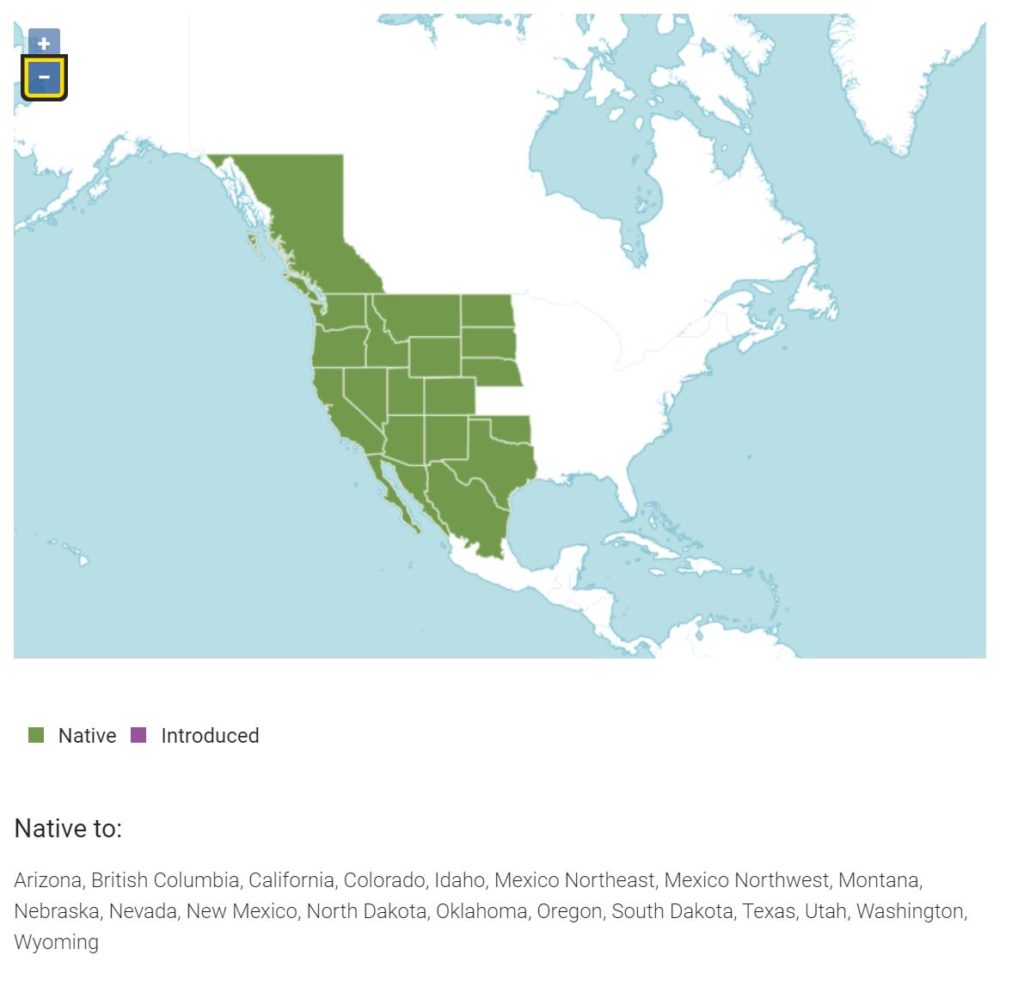

P. ponderosa is an evergreen conifer found in New Mexico from around 7,600-8,900 feet but it can exist outside this range in favorable conditions. This native species is the most widespread pine in North America and is an integral part of 65% of our western forests and 80% of the montane forests of the Southwest. One of the largest ponderosa forests extends from the New Mexico Gila Wilderness to the Coconino National Forest near Flagstaff, Arizona.

POWO (2023). “Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; http://www.plantsoftheworldonline.org/ Retrieved 27 November 2023.”

Pinus is Latin for pine and the species ponderosa means heavy, referring to the heft of the wood. Trees are the largest plants on earth and ponderosa are some of the largest. In the southern Rockies, they can grow to 160 feet with 50-inch diameters. West Coast giants can reach over 270 feet in height. It is also long lived. 700 years old is not unusual for a mature ponderosa. The oldest recorded Rocky Mountain ponderosa pine, 1,047 years old, was discovered in Colorado.

Ponderosas were first recognized as a new species in the 1820’s by the Scottish naturalist David Douglas who also realized the tree ring’s correlation to yearly growth. This led to the dating technique of dendrochronology developed by A. E. Douglass and the tree-ring dating of the ruins at Chaco Canyon from ponderosa lintels and vigas still extant in the structures. These trunks were dated to 850 CE.

Ponderosas grow in a broad variety of soils including rocky nutrient-poor sites. They tolerate both hot and cold temperatures and are very drought resistant, surviving with 6-foot taproots in permeable soil and 40-foot roots extending into cracks on rocky slopes. On steep slopes xylem cells (transport tissues that carry water and minerals from roots to leaves) can grow upward in a spiral, encircling the tree to distribute fluids more evenly.

Their preferred habitat however is in widely spaced stands with grassy understories and proximity to Gambel oaks (Quercus gambelii). Early travelers noted that ponderosa stands were often situated in open fields where lateral roots can reach 150 feet. Low intensity fires every 5 to 10 years had through the centuries kept these stands cleared, with the tree’s thick bark offering protection from the flames. But fire suppression in the 20th century stifled these fires and created more concentrated forest stands. In dense forest communities ponderosa roots only extend as far as the tree’s crown, making them less vigorous.

Ponderosa needles, as in many conifers, are leaves that have evolved by rolling up into compact needles. Bundled in 2s or 3s and up to 8 inches long, they have a waxy coating of cutin that reduces transpiration (evaporation of water). Ponderosa bark is distinctive. Young trees up to 100 to 150 years old, called “blackjacks” by early loggers, have an almost black bark that ages into golden brown scaly plates as thick as 3 inches, separated by dark furrows. The inner bark exudes a scent of butterscotch or vanilla.

P. ponderosa has been useful to mankind since prehistory. Native Americans and early settlers used all of its parts from the roots to the needles, from the bark to the sap for food, fodder, medicine, tools, fuel, dyes, waterproofing and just about anything else you can think of. Piñon nuts, not true nuts but seeds, were a staple food source for Indians of the Great Basin. Though ponderosa nuts are smaller, they too are edible.

Back to the amazing cones, the reproductive organs of conifers. Pines are gymnosperms, producing their seed in cones rather than fruits. Ponderosa pine cone production is sporadic, sometimes at intervals as long as 10 years. Both male and female cones emerge on the same tree. Male cones are short lived spongy brownish clusters usually situated on the new shoots of the lower branches to discourage self-pollination. They produce a powdery pollen in the spring that is wind dispersed, then they wither and drop off. First year female cones are pinkish bristles with soft scales located at the end of new growth shoots higher in the canopy. In their second year they develop into a compact oval with green scales, taking on a brownish hue in the fall. It can take over a year after pollen reaches the female cones in the spring to progress from pollination to fertilization through cell division and genetic reshuffling. After fertilization, seeds are produced and the ponderosa cone may take another year to fully mature into its 3-to-6-inch woody structure with prickled scales. Cones of different maturity levels usually exist on a single tree at the same time.

Here is the fun part. Pine cones can open and close their scales. This action is achieved by the difference in makeup and form of the internal and external surface components of the scales, which have opposing affinities for water resulting in uneven contraction or expansion. They open to receive pollen and close to protect the growing seeds after fertilization. Once mature, seed cones remain on the tree until conditions are optimum for seed release. Cold and damp conditions prompt scale closure; hot and dry weather activates scales to open, allowing the winged seeds to escape and reproduce. After the seeds are dispersed, the cones fall to the ground for us to collect for our wreaths and centerpieces.

References

Howard, Janet L. “Pinus ponderosa var. brachyptera, P. p. var. scopulorum.” U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory. 2003. Web. 26 Oct 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.fs.usda.gov/database/feis/plants/tree/pinpons/all.html

“I’m glad you asked: Pine cones.” UC Botanical Garden at Berkeley. 2022. Web. 26 Oct 2023. Retrieved from: https://botanicalgarden.berkeley.edu/glad-you-asked/cones

Oliver, William W. and Russell A. Ryker. “Ponderosa pine.” U.S. Department of Agriculture. Web. 26 Oct 2023. Retrieved from:

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654/volume_1/pinus/ponderosa.htm

Ponderosa pine in the Botanical Garden. Photo: Linda Churchill